The Biden administration unveiled a plan that would raise taxes on corporations to pay for its proposed $2.3 trillion for infrastructure.

In particular, talk of a global minimum corporate tax rate has gained new momentum after U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen raised it in a speech earlier this week, citing the need to avoid a "race to the bottom."

The main motivation behind this initiative would be to prevent or discourage companies from shifting their profits or residency to tax havens, as well as to put an end to "tax competition" between regions.

The establishment of a corporate minimum tax to discourage companies from filing taxes in countries with the lowest rates has been a key pillar of OECD discussions, but an agreement would not be easy to achieve:

But tax discussions are not just about permanent changes. This week the International Monetary Fund proposed a temporary 'solidarity' tax for pandemic winners and the wealthiest. High-income earners and businesses that prospered in the coronavirus crisis should pay additional taxes to show solidarity with those most affected by the pandemic, according to the IMF.

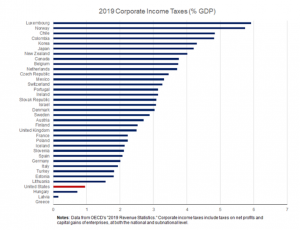

Corporate income tax collection in OECD countries as a percentage of GDP

Over the past two decades, the typical OECD country has collected about 3 percent of GDP from corporate taxes. And while the U.S. has historically raised comparatively less revenue through corporate tax relative to its trading partners, the gap was greatly exacerbated by the 2017 tax law. In fact, closing even half of the gap between the U.S. corporate tax burden and the OECD median burden is roughly enough to pay for the initiatives proposed in the American Jobs Plan.