At the beginning of the year, we argued that the risks of market corrections had been increasing(https://www.fynsa.cl/newsletter/estrategia-internacional-2/), due to higher interest rates as a result of the monetary normalization process undertaken by the Federal Reserve.

Fast forward to today and the S&P 500 accumulates a 6.0% decline for the year (which was up nearly 10% until just a week ago), while the Nasdaq given its heightened interest rate sensitivity, doubles the S&P 500's losses and beyond that the overall corporate earnings picture remains solid, concerns persist about Fed tightening and fears of stubborn inflation, which continues to feed back into highly stressed supply chains, energy prices pressured by geopolitical tensions (oil already trading at US$90 a barrel) and wage pressures that were most evident in this week's employment data.

To complicate matters, it is not only the Federal Reserve that has been raising the tone for an earlier and probably faster withdrawal of stimulus, but most major central banks (with the exception of China) are accelerating the withdrawal of stimulus.

First (among the majors) it was the Bank of England who surprised investors with a rate hike in mid-December (after promising they wouldn't), only to end QE (asset purchases) this week and raise rates again.

Also this week, President Lagarde of the European Central Bank (ECB) signaled an aggressive policy shift, given the heightened inflationary risks, with a substantially earlier policy exit now expected.

Even speculation about the normalization of monetary policy has reached Japan, the most moderate of all developed countries.

In practice for the US case, the market is already incorporating 5 rate hikes by the end of the year (and a 25% probability of a 50 bp hike in March), asset purchases would end in March and even an early start of QT (balance sheet reduction) is being priced in.

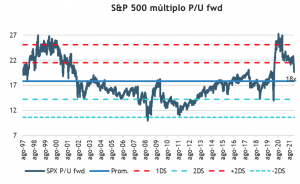

Against this backdrop, interest rate pressures remain high putting pressure on market valuations. From a fundamental perspective, rising interest rates have accounted for the entirety of the S&P 500's decline. The 10-year US Treasury real yield increased by 60 bps (-1.1% to -0.5%) between the S&P 500's all-time high on January 3 and the day after last week's FOMC meeting. Over the same period the S&P 500 P/U fwd multiple went from 21.8x to 19.5x, matching the market decline.

Of course, a recurring question these days is whether the worst of this adjustment is over or whether we may still face further losses until markets stabilize. For reference, all else constant, the S&P 500 would fall approximately an additional 10% to 4,000 if the Treasury yield in real terms were to rise from the current -0.6% to 0% and 15% to 3,800 if it were to rise another 50 bps.

In this sense, an S&P 500 at 4,000 points would be consistent with a reversion to the mean in terms of valuation (around 18x) and surely a great buying opportunity .

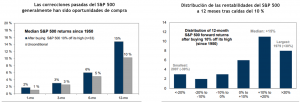

Somehow "we were a little bit bad used to it" with adjustments that during 2021 did not exceed 5% and that the market quickly went out to buy them. In fact, we ourselves promoted "buy the Dip" many times, but evidently things have changed. But the question remains, are corrections of 10% or more so infrequent without reaching a bear market (declines in excess of 20%). The evidence shows that they are not.

There have been 33 S&P 500 corrections of 10% or more since 1950. The median episode lasted approximately 5 months and encompassed a peak-to-trough decline of 18% (which in practice would be consistent with an S&P 500 around 4,000 points). An investor buying the S&P 500 10% below its high, regardless of whether it was the low, would have earned an average return of 15% over the next 12 months (positive 76% of the time) and corrections rarely turn into bear markets unless the economy is headed for a recession (which is not our base case).

Source: Goldman Sachs

Our recommendation has been to be very conservative in terms of duration because of the risks of higher interest rates. But, just as in equities we talk about "mean reversion" in terms of valuations, in fixed income one can apply a similar approach.

Corporate spreads for the IG US category have moved up in the order of 25 bps, a relatively tight and orderly move. It makes sense, the economy is performing and corporate balance sheets are robust. But with the increased interest rate pressures, we should not be surprised to see additional rate hikes to converge to average levels of 130 bps (a move very similar in practice to the tapering of 2013).

A positive derivative that should be evaluated as an opportunity is that yields are starting to look more "seductive". Today the category offers a yield of 2.8% (which could approach 3%), that's more than 100 bps from only 6 months ago and in a world with so little to offer they will surely fight it out.

Humberto Mora

Strategy and Investments