We believe we are at an inflection point of some important structural changes. The post-pandemic cycle is driving higher inflation and interest rates.

As inflationary pressures become more evident, following this week's US inflation data that left 12-month consumer prices at 7.5%, markets are beginning to lean towards faster and probably more aggressive monetary normalization. In practice, we went from pricing in five rate hikes by the Fed a week ago, to seven hikes in 2022 (i.e., a 25 bp hike per meeting), with the probability of a 50 bp hike at the March meeting growing.

Clearly this has shifted the entire rate curve, with 10-year treasuries trading above 2.0% and no foreseeable ceiling at the moment (something closer to the 2.3% - 2.5% range seems reasonable to us).

As we move through this inflection point, market drivers and leadership styles are likely to change. The drivers of returns and market leadership should be very different from the last cycle and should result in a different approach to investment strategy.

The inflection of interest rates

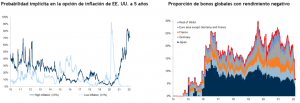

The rise in inflation expectations has been rapid. The aftermath of the financial crisis saw a sharp drop in aggregate demand and inflation. Inflation expectations fell and the implied probability of high inflation above 3% collapsed; while the probability of inflation below 1% (the light blue line) increased. This has now reversed.

As a result, the change in interest rate expectations has been exceptional. As recently as June of last year, the market expected no interest rate hikes in 2022 in the U.S. and as we discussed earlier now quotes seven hikes by the Fed. Similarly, the radical change in forward guidance at other central banks has been exceptional. The UK rate hike to 0.5% was achieved in consecutive meetings for the first time since 2004 and was the largest meeting-to-meeting change in the average vote since 1997. In Europe, the epicenter of deflationary fears a few years ago, the market is pricing in a zero deposit rate for the first time since 2014.

The inflation transition, coupled with more aggressive central banks, has resulted in a sharp decline in the proportion of negative-yielding bonds worldwide, from around 25% to 5%, and the value of such bonds has fallen from a peak of US$18 trillion three years ago to around US$5 trillion today.

The impact of higher interest rates on equities

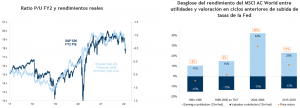

The first is that rising interest rates have pushed down valuations.

This is not unusual. In recent cycles, while interest rates have generally risen (the extent of which was largely dependent on the strength of the economy), stocks have always been downgraded and ultimately positive performance has been driven by corporate earnings.

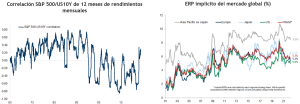

The second impact is that correlations and risk premiums have started to move:

The correlation between stock and bond prices has been negative for most of this century. As bond yields fell to unusually low levels, further declines in yields (or rising bond prices) were often accompanied by weaker stocks. This made sense in a world dominated by recession and deflation risks. The rise in inflation that has pushed bond yields higher in recent weeks has pushed stocks lower, resulting in a positive correlation.

The shift from deflation to inflation as the main risk is significant. During the post-financial crisis era, the collapse of inflation expectations and the presence of central bank buying programs reduced term premia in bond markets and, at the same time, raised risk premia in equities (which have more to lose from recession and deflation). The end of QE (asset purchases) and the shift to QT (asset sales), along with higher inflation, should shift the balance in the opposite direction, which would reduce the ERP, something we have seen over the past year and probably have further to go.

Turnover at Value

In the last cycle, investors were attracted to growth stocks. As aggregate demand collapsed, inflation expectations fell and so did nominal GDP along with long-term income growth assumptions. Growth became scarce and more valuable. Lower and lower rates increased the relative value of longer-dated assets.

In the decade following the financial crisis, asset markets were repriced by declines in the risk-free rate. The following charts show different measures of "inflation" in the QE-driven world from 2009-2020. In the first chart, inflation in the real world (the light blue bars on the right side) was very low: consumer prices, wages, etc., barely moved and commodity prices fell; interest rates collapsed and central banks printed money. Meanwhile, inflation in financial assets (on the left in dark blue) was very high and real yields were extremely strong. The best performers were the longer-dated assets: Nasdaq, S&P 500 and growth stocks in general.

If we contrast this with the inflationary decade of 1973-1983, we find a very different pattern. Most assets failed to achieve a real return as yields fell below consumer prices. The best performers were "real" assets and commodities. The worst performers were longer duration stocks: S&P and Nasdaq. While 1970s-type inflation is unlikely, it may well be a guide and makes the current market action toward value investments seem rational.

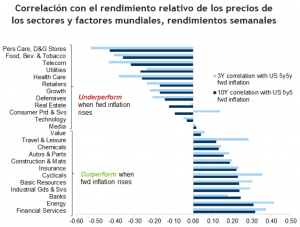

The rotation towards Value in recent months is a reflection of the inflation inflection point. As the chart below shows, looking at the correlation between relative sector performance and inflation expectations shows something similar. All the sectors that serially underperformed in the post-financial crisis cycle (which was dominated by deflationary fears) are those that are positively correlated with inflation expectations: energy, banks, resources.

Recommendation

Our view, for several months now, is that we believe we are entering a "more inflationary" cycle change, unlike the last decade which was basically deflationary. Therefore, we are favoring short duration value investments (and therefore less sensitive to interest rate hikes) and positioning for a steeper curve (financial sector, energy). We are looking for more diversification outside the US in developed markets where valuations are more attractive (Europe and Japan), as well as in emerging markets that could start to outperform in 2022, as China eases monetary policy.

In fixed income, maintain a very conservative strategy in terms of duration.

Humberto Mora

Strategy and Investments